It’s easy to tell the truth, yet in business, some brands still stretch or blur it to get attention.

Brands exaggerate for all kinds of reasons — competition, pressure, or poor oversight — but in advertising, those exaggerations are public, and the fallout can be costly. Phony stats. Photoshopped models. Hidden fees. Misleading labels. These aren’t accidents; they’re examples of false advertising, and they happen more often than you’d think.

For brands running campaigns or shaping messaging, getting it right isn’t optional. Tools like brand asset management software help teams stay honest, consistent, and legally sound before a small oversight becomes a serious issue.

What is false advertising?

False advertising refers to any misleading, deceptive, or outright false claim made in an advertisement about a product or service. This can include exaggerating benefits, omitting important details, using manipulated visuals, or making promises the business can’t keep.

In simple terms, if an ad gives customers the wrong impression about what they’re buying, how much it costs, or what it can do, it may qualify as false advertising under consumer protection laws.

TL;DR: Everything you need to know about false advertising

- What is false advertising? False advertising refers to making misleading or false claims that give consumers a wrong impression about a product or service.

- What are the main types of false advertising? The main types of false advertising include bait and switch, omission, quality or origin deception, hidden fees, and puffery.

- Is false advertising illegal? Yes. False advertising violates consumer protection laws and can result to fines, lawsuits, and enforcement actions by the FTC.

- What’s new in false advertising for 2025? Regulators are cracking down on AI-generated claims, hidden fees, and fake “Made in USA” labels, with major cases such as Match Group’s $14 million settlement.

- What are the consequences of false advertising? False advertising can result in legal penalties, ad removals, consumer refunds, and serious reputational harm.

- How can brands avoid false advertising? Brands can prevent false advertising by verifying claims, disclosing all relevant costs, avoiding exaggeration, and conducting regular compliance reviews.

- What tools help prevent false advertising? Brand asset management, compliance, and social media monitoring software help ensure truthful, transparent messaging.

- Why does honesty matter in false advertising prevention? Because transparency builds consumer trust, protects your brand, and ensures compliance with advertising laws.

What are the different types of false advertising?

We lie for many reasons, but desperation is definitely one of them. The same goes for companies that aren’t making enough money to stay afloat. Here are the types of false advertising to look out for as a consumer. Some of them are awfully slick.

1. Bait and switch

Bait and switch advertising occurs when a company advertises a product or service that they don’t intend to sell or provide to consumers. This is done in order to lure customers into their store or onto their website, only to pull the bait out from under them and attempt to sell another product or service in its place. Advertisers don’t even have to completely omit the truth from their advertisements to get in trouble for this.

Nobody’s getting free beer at this bar.

Source: Toronto Realty

2. Lying by omission

Arguably one of the most common ways to lie in an advertisement, lying by omission involves simply removing relevant information from an advertisement to make sure that the best features of a product or service stand out with no distractions.

For example, if a company hypothetically designs an advertisement for a battery that says “Lasts Even Longer”, this would be considered lying by omission. Lasts even longer than what? A potato?

The Procter & Gamble Company was sued in the United States in 2012 by customers for delivering misleading information. It turned out that not only did they omit what batteries they lasted longer than, but that the entire claim was an outright lie as the batteries, while more expensive, did not last longer than traditional alkaline batteries.

Source: Duracell

3. Quality or origin deception

It’s illegal for a company to make a false claim about the quality or origin of the product that they’re selling. It’s also illegal for a company to withhold information about defects that they’re aware of.

This includes claiming that a food is 100% organic when it’s not, claiming that something was manufactured in the USA when it was manufactured overseas, and omitting known defects from warning disclosures.

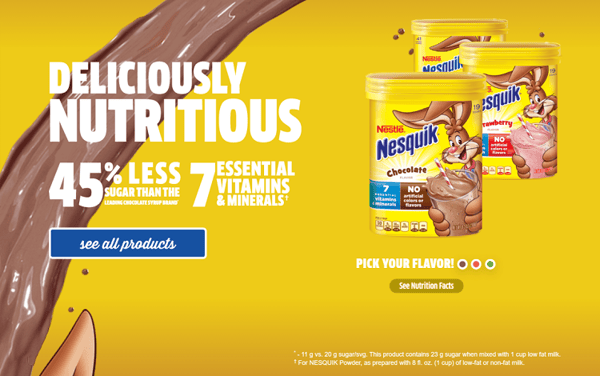

Source: Econsultancy

In bold, Nesquik’s copy reads “45% less sugar than the leading chocolate syrup brand*”.

In fine print, it reads: “ ~ 11g vs. 20 g sugar/svg. This product contains 23 g sugar when mixed with 1 cup low-fat milk”.

This ad is the revised version of the even more deceptive one that came before it.

Photography is an extremely popular way to go about this form of false advertising. Editing photos to make models look thinner, food to look juicier, and rooms to look brighter has been around since the dawn of time. Photoshop is powerful, but that doesn’t mean that power should be used for evil.

Using your Photoshop powers for good? Let others know what you think about its capabilities:

4. Hidden fees

That fine print can be really tricky. Another popular way to falsely advertise a product or service to make it look more attractive is by not fully disclosing the actual price. Completely omitting a service charge, maintenance fee, or equipment fees is asking for a court case.

Often, advertisers attempt to get around this with fine print, which is still considered deceptive. The FTC regulations state that in order for an advertisement to be lawful, all terms and conditions must be clear and legible. Advertisements that say something is 5 payments of $19.99 won’t fly.

5. Puffery

Think about a pufferfish. Those little guys really know how to blow themselves out of proportion. Advertisers follow suit by making statements that are so broad and unbelievable that they’re both impossible to prove and disprove, making them difficult to challenge to court.

Note that almost every movie is #1. Every fast food restaurant is the “fastest”. Any advertisement claiming that their product or service is “the best”.

Puffery is a filler statement in advertising to make an average product or service sound better than its competitors when the product or service really has no other way to stand out.

Bigger than bigger? What does that even mean?

Source: Inverse

Is false advertising legal?

No, false advertising is illegal in many jurisdictions, including the United States. Consumers have a fundamental right to truthful information about the products or services they’re buying: what they are, what they cost, and what they actually do.

What’s new in 2025?

- The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has sharpened its focus on emerging ad practices, including AI‑driven claims, hidden fees, and “Made in USA” origin labels.

- A major 2025 settlement: Match Group agreed to pay $14 million (without admitting liability) after the FTC alleged deceptive subscription and cancellation practices.

- The FTC has flagged the “all or virtually all” standard for origin claims (e.g., “Made in USA”) and intensified enforcement.

- Regulators and courts are also confronting insurer coverage gaps. Many liability policies do not cover false advertising risks, despite the increasing prevalence of litigation.

What counts as false advertising under U.S. law?

A business may face civil or regulatory action if it:

- Makes false, misleading, or deceptive claims about a product or service.

- The claim is material (important to the consumer’s decision) — e.g., “Made in USA”, “health benefit”, “free trial”.

- A consumer saw the advertisement and depended on it.

- The consumer purchased the product/service (or was induced to do so) because of the statement.

Additionally:

- Competitors can sue under the Lanham Act for unfair competition caused by false or misleading advertising.

- State consumer-protection laws also apply. For example, many states permit private lawsuits for deceptive advertising practices.

What are the legal remedies and consequences?

When liability is established (or settled), possible outcomes include:

- Injunctions: the advertiser must stop running the deceptive ad or revise it.

- Corrective notices: The company may need to publish clarifications or call-outs affirming the truth.

- Monetary remedies: fines, civil penalties, restitution to consumers, and damages to competitors. In recent cases, penalties have reached millions of dollars.

- Reputational harm: beyond direct legal risk, enforcement actions generate negative publicity and reduced consumer trust.

With digital advertising, influencer marketing, and AI-driven content all on the rise, regulators are facing new layers of risk. The FTC and other agencies are reacting accordingly: unlimited ad channels mean unlimited potential for deception, which in turn means increased liability for brands.

How to avoid false advertising

Avoiding false advertising isn’t just about staying out of legal trouble; it’s about building long-term brand trust. Every claim, image, and headline you publish shapes how consumers perceive your integrity. For brand managers and marketing teams, prevention starts with systems, not last-minute reviews.

Here’s how to ensure your advertising stays accurate, transparent, and compliant without killing creativity.

1. Verify every claim before you publish

Before any campaign goes live, ensure all performance claims, statistics, or testimonials are backed by reliable data.

- Require proof or source data for every measurable statement (“reduces costs by 25%,” “clinically tested,” “made in the USA”)

- Keep documentation — lab results, market studies, or customer surveys — in a shared compliance folder

- Set a standard approval checklist inside your brand asset management software so that all ad assets pass through claim verification

2. Be transparent about pricing and terms

Hidden costs and misleading “free” offers are among the most common triggers for FTC action.

- Disclose all pricing terms, subscription renewals, shipping costs, and trial expiration dates clearly and prominently

- Avoid “fine print” or buried disclaimers — regulators now expect plain-language disclosures in the same visual frame as the offer

- Conduct a price-accuracy audit before publishing promotional campaigns

3. Avoid ambiguous or exaggerated language

Phrases like “best,” “fastest,” “only,” “clinically proven,” or “100% guaranteed” are red flags if they can’t be substantiated.

Ask before you approve:

- Can this claim be objectively proven?

- Would an average consumer reasonably interpret it as a fact, not opinion?

- Is it puffery (subjective) or a verifiable statement (factual)?

Maintain a “red flag words” list inside your marketing style guide, so future campaigns stay compliant by design.

4. Standardize your internal review workflow

Consistency is your brand’s best defense. Implement a formal approval pipeline for all ad materials to minimize risk.

Suggested review flow:

- Creative team drafts ad copy and visuals

- Brand team checks tone, voice, and alignment

- Legal/compliance verifies factual accuracy and disclosures

- The executive or campaign owner provides the final sign-off

- Assets are archived in a digital asset management (DAM) system for audit traceability

Tools like compliance software automate this workflow, flagging risky claims, maintaining approval logs, and ensuring that nothing goes live without review.

5. Keep influencer and UGC content in check

Third-party endorsements can still trigger liability if they’re deceptive or undisclosed.

Protect your brand by:

- Ensuring influencers use clear disclosure tags (#ad, #sponsored)

- Reviewing affiliate or partner content for accuracy and alignment

- Storing influencer contracts and content approvals in your compliance system

- Monitoring live campaigns for deviations from approved messaging

Best influencer marketing software in 2025

- Captiv8 for affiliate networks, data imports and exports, and social commerce. (Available on request)

- Later Influence for influencer recruitment, influencer segmentation, and campaign analytics. ($16.67/mo)

- impact.com for partnership management, influencer payments, and performance analytics. (Available on request)

- Afluencer for e-commerce integration, influencer scoring, and audience analysis. ($49/mo)

- GRIN for influencer collaboration, reporting, and dashboards, and influencer recruitment. (Available on request)

These influencer marketing software are top-rated in their category, according to G2’s 2025 Fall Grid Reports. I’ve also added their monthly pricing wherever available.

6. Train your teams on advertising ethics

False advertising often stems from ignorance, not intent.

Conduct quarterly workshops that cover:

- What qualifies as misleading or deceptive advertising

- How to handle consumer complaints

- FTC and state-level ad regulations

- Case studies of recent brand fines

7. Use technology to support transparency

Modern marketing ecosystems are too complex for manual policing. Invest in tools that enforce compliance without slowing down creativity.

Recommended software categories:

Together, these platforms reduce human error and create an end-to-end record of compliance.

8. Stay ahead of legal and industry changes

False advertising laws evolve as fast as digital channels. In 2025, regulators are targeting:

- AI-generated claims and manipulated visuals

- Deceptive origin labels (“made in USA”)

- Hidden subscription fees

- Synthetic testimonials or fake reviews

Set up Google Alerts or subscribe to FTC/ASA newsletters to keep your team informed about policy updates.

False advertising: Frequently asked questions

Q. Is puffery the same as false advertising?

No. Puffery refers to exaggerated, subjective claims, such as “the best coffee in the world,” which are typically considered legal. False advertising involves factual claims that can be proven false or misleading, like “clinically proven to cure acne”, and can lead to legal penalties.

Q. Is it false advertising if an influencer makes the claim, not the brand?

Yes, under FTC guidelines, brands are responsible for the claims made by their influencers, affiliates, and endorsers. If a sponsored influencer makes a misleading or unsubstantiated claim, your brand can be held liable, especially if there is no clear disclosure (such as #ad or #sponsored).

Q. Can AI-generated ads be considered false advertising?

Yes. In 2025, regulators are increasingly monitoring AI-generated claims, imagery, and testimonials. If AI-generated content misleads consumers or fabricates product performance, it can still trigger false advertising liability, even if no human wrote it. The FTC has made it clear that AI does not absolve responsibility.

Q. Do disclaimers in fine print protect you from false advertising claims?

Not necessarily. If a disclaimer contradicts or “fixes” a misleading headline, it may still be considered deceptive. The FTC requires that all material terms be “clear and conspicuous,” which means no hiding essential conditions in fine print or hard-to-read text.

Q. Are visual edits, such as photo retouching, considered false advertising?

Potentially. Visual deception (e.g., digitally enlarging product size, altering model appearance, exaggerating product performance) can qualify as false or misleading if it sets unrealistic expectations. In regulated industries such as cosmetics, food, or automotive, this type of “visual puffery” can draw scrutiny from watchdog groups and regulators.

Brand trust starts with truth

In a competitive market, it’s tempting for brands to push the boundaries of what they say, show, or promise. But when advertising crosses the line from persuasive to deceptive, the fallout isn’t just legal, it’s reputational. The most valuable asset your brand owns isn’t a slogan or a logo. It’s trust, and every honest campaign builds it.

Monitor claims across channels with social media listening software to unify analytics.

This article was originally published in 2019. It has been updated with new information.